Co-Founder Jeff Geoffray interviewed on Film Daily

In the sanctum of New Orleans’ Adult Education Center, Jeff Geoffray, a cinematic virtuoso, finds himself retracing the steps of the ghosts of a bygone era. Jeff’s legacy, interwoven with the indomitable spirit of his mother, Alice Geoffray – a luminary in education and a bulwark against injustice – and the insightful fervor of Tim Gibbons, conjures a symphony of history that whispers tales of struggle, hope, and resilience.

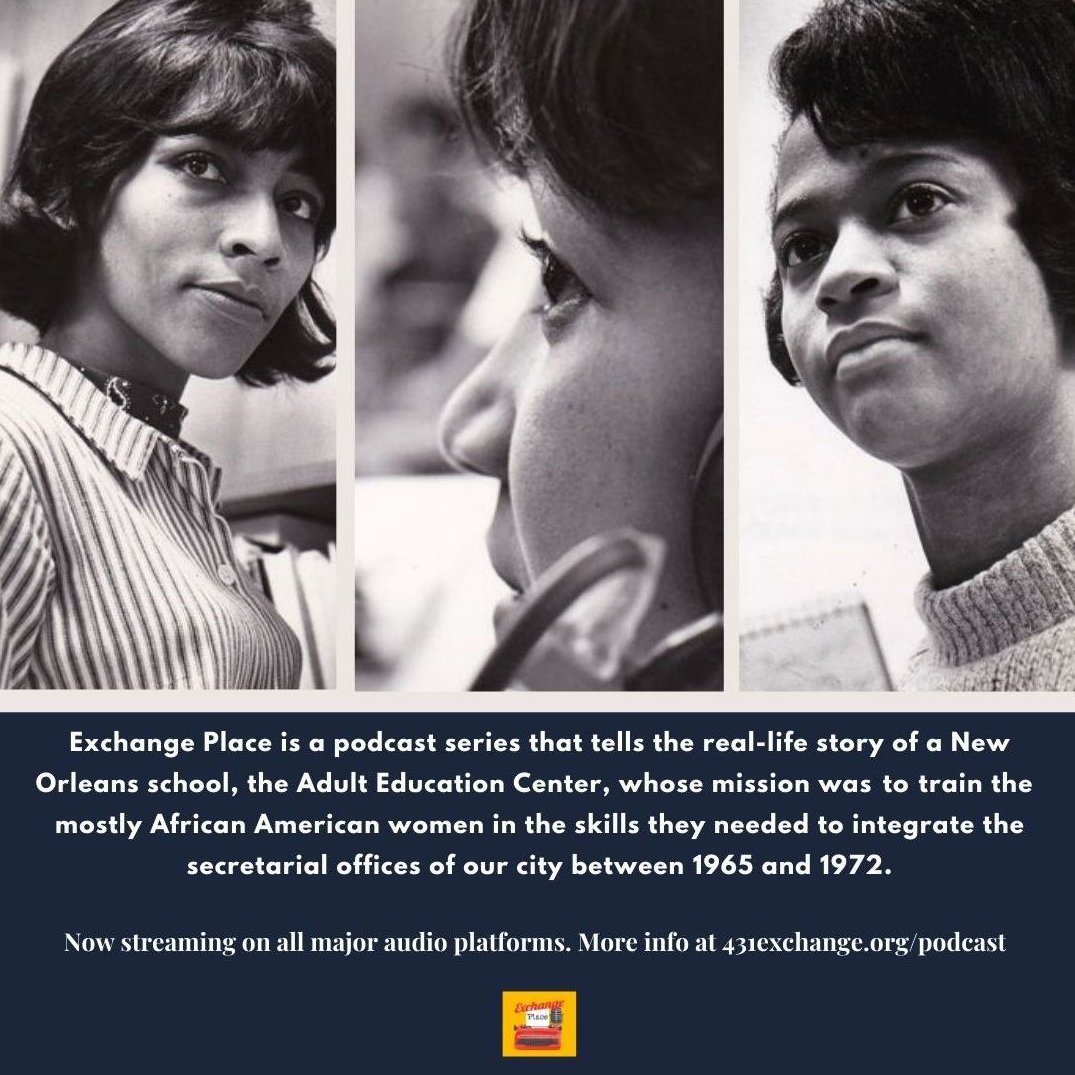

The Adult Education Center was a pivotal program in the fight for equal job and adult educational opportunities.

Blue Rider Pictures, the vessel that carried him through the cinematic waves, now embarks upon an odyssey across time, where each echo in the hallowed halls is a note in the chorus of history.

Today, as we converge with Jeff Geoffray, we’re not just engaging with a man, but entwining with the very strands of time. With Alice’s graceful fortitude as his beacon, and flanked by allies such as Walter Josten and Amy Taylor, Jeff translates the echoes of a forgotten past into an urgent clarion call.

Our interview follows his tapestry, woven with ink and celluloid, is an homage that yearns to reverberate through ages.

Jeff, as an executive producer, what elements of this story made you decide to get involved?

The dramatic transformation of the students, teachers, and the New Orleans business community that I witnessed first-hand while visiting the Adult Education Center was what caused me and others to encourage my mother to write her memoirs. My business partner at Blue Rider Pictures, Walter Josten, felt the same way.

But, it wasn’t until my sister, Jeanne, and I interviewed Tim Gibbons, the founder of the program, that I became confident the story of the school had all the elements that would make for a great book, podcast, documentary and, ultimately we hope, a dramatic television series.

Whereas Alice was nostalgic about the summer of 1965 when the program started, Gibbons was focused on the dangerous undercurrents that were swirling around the school at the time and threatened its existence. Before the summer ended, he was removed from his post in New Orleans and sent a thousand miles away to one near Albuquerque, New Mexico.

What Gibbons helped us realize is that progress in civil rights and, in particular, progress toward equal educational and employment opportunities was not inevitable. Formidable and dangerous obstacles were in the way that had been centuries in the making; and would not go away even with changes in laws and practices.

Storywarrior Media is known for its animated features. What compelled you to transition to a historical and socially impactful project?

I have always been interested in non-fiction especially socially impactful material. Walter Josten, my partner at Blue Rider Pictures, was very passionate about historical biographies and, together, we developed a film about Father Damien, now Saint Damien, who championed the rights of the leprosy patients on the island of Molokai who had been abandoned by society and even the church.

The students, taught and nurtured by their own resilient segregated Black communities, were the ones who had something to teach their society.

Ultimately, we made an award-winning documentary narrated by Robin Williams called Uncommon Kindness. Walter is now developing a television series on the subject. At Storywarrior, my business partner and writer, Amy Taylor, fell in love with the story of the Adult Education Center, especially after meeting some of the graduates and hearing their stories.

She was the first to encourage us to record a podcast consisting of interviews with the graduates especially after reading the transcripts of the many interviews I had already conducted. For over thirty years my focus was on producing and executive producing movies. I have credits on over one hundred fifty films representing over $1 billion of production.

Starting in 2018 I put all other projects on a back-burner devoted myself full-time to finishing the book Alice started and, co-founding with Jeanne, the non-profit organization that honors the legacy of the Adult Education Center, The 431 Exchange.

Can you share your personal memories of Alice Geoffray growing up, and how do you feel they shaped your career choices?

My mother had an expression, “do your best and offer it up to the Lord.” If you’re not religious, you might say, “leave it all on the court.” My mother loved her work and her family and, whether it was being a teacher, administrator or parent, she always did her best even if it meant working long hours.

She was usually the last to leave the office and the first to be there if you were in the hospital or needed to talk to someone who would listen deeply without judgment. Over the past five years Jeanne and I have read thousands of pages of her writing, including the all-important and voluminous annual reports she compiled for the federal government and sponsors of the Adult Education Center; and reports and grant applications for her later work.

What is incredible is that in all that writing, all of which she typed herself, there are no mistakes, no typos, nor grammatical errors! Not a single one. One time, I thought I spotted a mistake – a misplaced comma. I was so excited I called up Jeanne to tell her. But, in reading back the sentence, I realized there was no mistake. I just hadn’t understood the sentence syntax.

On top of her attention to detail, she always made a point of personalizing whatever she was writing, even if it was a government report or a letter to the President of the United States. She had a knack for humanizing even complex topics. Her writing had a sparkle to it. As in my work producing films, In making the choice to devote myself to telling this story, Alice inspires me to do my best. To leave it all on the court.

What unique challenges did you encounter in transitioning Alice Geoffray’s story to the podcast?

After finishing the second draft of the book, Exchange Place, our editor, Leslie Guttman, passed away from a COVID related illness even though she was only in her mid-50’s. Before she died, Jeanne and I had developed a deep professional and personal relationship with Leslie. In fact, I would say it was the most substantive creative collaboration of my career.

Guttman, a journalist, author and long-time writer for the San Francisco Chronicle, taught me more about writing than anyone else. In particular, she taught me how to process criticism. I think that made me a smarter writer, one who could learn from my mistakes. Leslie’s death along with input from a new editor, Evelyn White, caused me to put the next draft of the book on hold and pivot to the podcast. The main reason for doing so was that I felt I was not fully representing the voice of the Adult Education Center’s alumnae in my writing.

That, together with Leslie’s passing, created a sense of urgency in me to do more formal recordings with the alumnae so that they could share their transformational stories with the world directly. This pivot was a challenge during COVID as we could not do the recordings in person.

But, moreso it was a challenge because we had in mind an ambitious podcast format with interviews, narration and music. Furthermore, we did not have technical experience with hosting, recording, editing and/or distributing a podcast. Good thing we didn’t know how hard it would be when we started! We’ve learned much in the process and are grateful to all those who worked on the podcast over the past two years.

The school’s first class was shut down due to racial tensions. How do you portray this controversial part of history in your series?

We portray the school’s first class being shut down by telling the story of Father Gibbons who had arrived in New Orleans from the Midwest in 1959. Gibbons was informed and inspired by civil rights leaders in the city’s Black community, especially a young Norman Francis who would later become the President of Xavier University.

Building a just society with equal educational and career opportunities for all its members is not inevitable – to reach this goal every institution must be aligned in favor of it, each individual must play a part in making it happen.

Amongst his other ties to the Civil Rights movement, Francis helped aid wounded Freedom Riders whose first travels into the Deep South to assist in voter registration efforts were met with violence. Gibbons was raised in an all-White farm town in Illinois. New Orleans was essentially his first post after he joined the Catholic clergy.

It was Francis who guided Gibbons to focus on helping to improve employment opportunities in the Black and poor White community. It was Francis who encouraged Tim to focus on jobs, such as business and secretarial jobs, that were in demand but off limits to Black Americans.

Gibbons started the pilot program for the Center in a building adjacent to the Dominican College campus. Dominican’s neighbors complained about the presence of the pilot program’s students in their neighborhood. Gibbons helped Dominican resist the threats and intimidation until a city inspector was called in and threatened to condemn the school’s property.

Only then did Dominican back down. The pilot program was closed but they had gathered enough data to prove to the MDTA (Manpower Development and Training Act) authorities, Department of Labor and HEW (Health Education and Welfare) department that a program of its kind was in dire need.

We did not know about the school’s pilot program being shut down until we interviewed Tim Gibbons in 2018. Nor did we know the reasons why he was removed from his post in New Orleans, reasons that had to do with an incident that involved the Deep South’s antipathy toward both organized labor and progressive causes.

Alice Geoffray was a 41-year-old grandmother, sole support for her seven children, and a transformative figure in this story. What characteristics of hers do you believe were key to her success?

If Alice had one superpower it was empathy. She had the ability to shed her assumptions and presumptions about a person and listen. In the case of the students at the Center she could relate to their positions as mothers. She could relate to the younger women, too, as a mother would. Later in life, she worked on her powers of empathy to understand the unique challenges that men, especially Black men, and men-of-color, face. She did this by educating herself and working side-by-side with men in the school system and elsewhere.

Secondly, she was constructive. From the outside her life may have seemed messy. She was separated from her husband; she was the sole support for seven children; she often did not feel good about her personal appearance; and, she entered the work force and upper education at a late stage in her life and career.

On the inside, she could feel depressed, feeling like she had not lived up to her own expectations especially in terms of being a positive force in other people’s lives. But, in fact, all her actions, personally and professionally, were purposeful.

She did not waste time hating or hurting others, nor was she self-destructive. She was always building something worthwhile, building a family, building close personal and professional relationships, building educational programs.

How are you ensuring the representation of the experiences of the African American women who attended the school and later integrated city businesses?

There are tropes that have evolved, not only in Hollywood, but also in how American history has been told, that we are trying to avoid. For instance, the trope of the White savior. While our mother was the director of the school, it was the students who took the risks and did the work that made it possible for them to become successful.

The goal to reinforce students’ self-image led to teaching Black history, an unheard of practice at the time.

When we say that the school changed the moral skyline of New Orleans, we show how the students were the ones who caused that change. The American system of apartheid that was entrenched when the school was in development had no positive moral lessons to impart to the students. It was the other way around.

The students, taught and nurtured by their own resilient segregated Black communities, were the ones who had something to teach their society. They were the ones who helped their city and other cities to transition from a world as oppressive as the one depicted in A Handmaid’s Tale to the one depicted in Mad Men where their first jobs were to be found.

Their example, told in newspapers and on television, inspired other women around the country. Meanwhile, educators like Alice, businessmen like James Coleman, Sr., and politicians like Congressman Hale Boggs did their utmost to, as Ms. Connie Payton (Class of 1970) would say, ‘have their backs.”

Or as Ms. Patricia Morris (Class of 1967) states, “you can’t have love without respect and we felt the teachers and advisors respected us.” Our podcast, in part, tells the story of how and why the teachers grew to have such respect for the students and their triumphs.

How do you plan to depict the concept of Alice Geoffray as a “Fairy Godmother” to the 431 “Cinderellas” attending the school?

Alice is quoted on many occasions as saying she felt like she was the “Fairy Godmother to 431 Cinderellas.” Likewise, graduates are quoted as saying that the school’s landlord, businessman, James Coleman, Sr., who rented a space to the school after fifty-nine other landlords turned them down, was like a Fairy Godfather.

But there are feminist authors and others who criticize what they call ‘Cinderella syndrome’ and ‘fairy tale’ thinking. That is, the tendency to think that someone else will come along to solve your problems. That ‘one day my prince will come.’ As we took our own critical look at Alice’s quote it helped us focus on aspects of the Cinderella story that diverge from the pejorative view of fairy tale thinking.

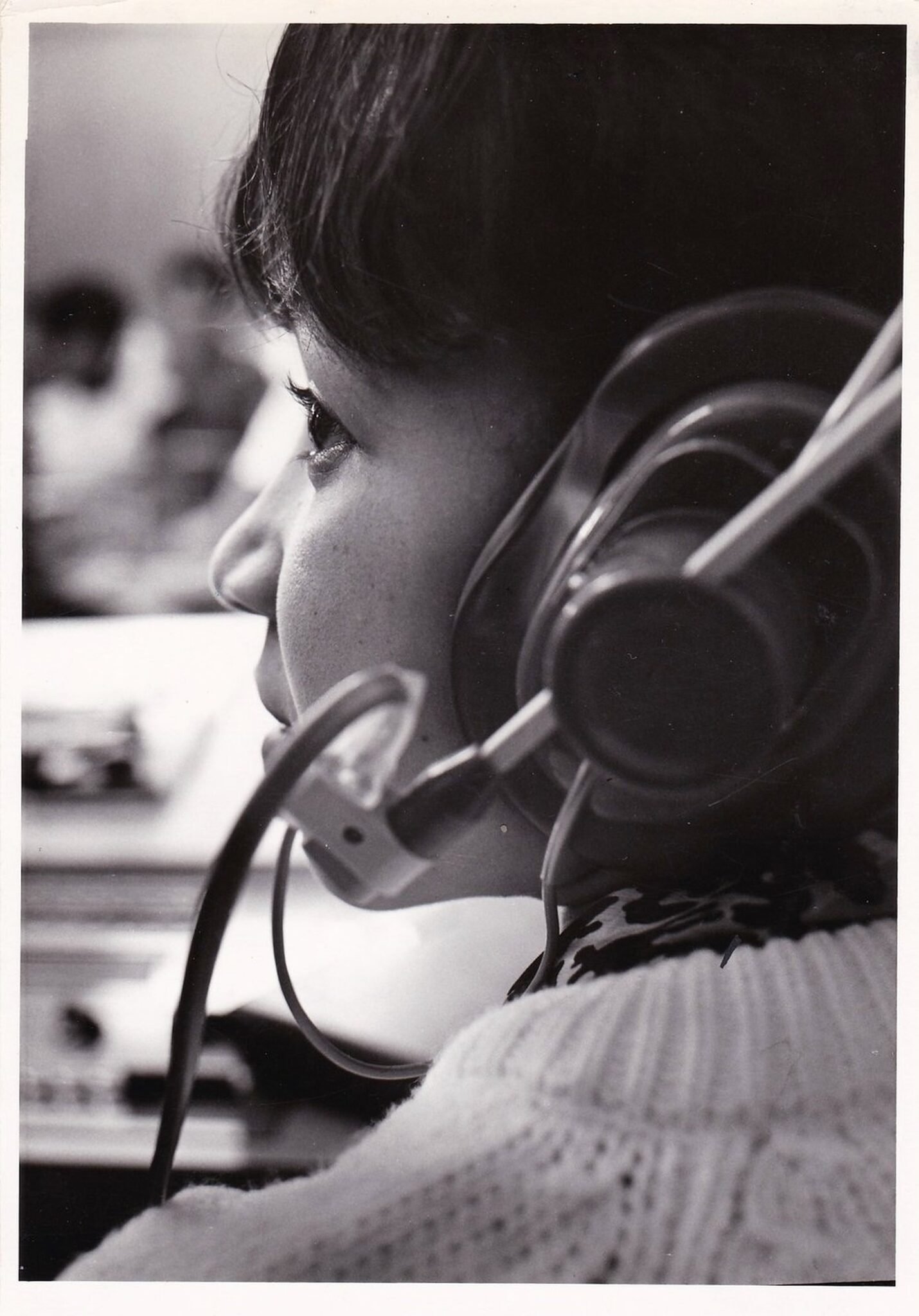

In our story, the magic that the teachers impart to their students are the soft and hard skills that give them a competitive advantage in the workplace. For instance, the students were trained on state-of-the-art equipment such as the IBM Selectric typewriter that was not yet dominating offices but would in the following years.

The students were taught how to language shift from the language they spoke at home to what the school called Business Speech and back again so they could not be discriminated against in job interviews or in the workplace, at least, because of their speech patterns.

The Center published the first book on teaching English as a second language in this context and placed an emphasis on respecting the students’ original language by identifying difference between it and the target language versus taking a corrective approach. In general, the school took a non-assimilationist approach in their curriculum although they would not have used that term back in the day.

Their goal to reinforce their students’ self-image led them to teaching Black history, an unheard of practice at the time. Continuing with the Cinderella metaphor, the Fairy Godmother works with Cinderella from the start because Cinderella is filled with a grace that her evil stepsisters and stepmother do not have.

In our story, we use facts about the students’ lives before they even enter the Center’s program to upturn all kinds of notions and prejudices about the desires, ambitions and capabilities of women who are on welfare, have large families, or have lived in housing projects.

Finally, it was Cinderella who makes the big leap to go to the ball and ultimately charms the Prince and the rest of society. She’s the one who takes the risk and earns the reward. In our story, the Ball is an equal educational opportunity and the job market. The students don’t wait for a prince to arrive.

Many of them quit their domestic jobs or made other sacrifices to attend the school’s intensive training for nine months, knowing that such job programs were notorious for being ineffective. Without ever making reference to the metaphor as outlined above, we used our critical analysis of this fairy tale to better understand the qualities of the alumnae that Alice was referring to when she called her students by the eponymous title.

Alice Geoffray’s transition from a more passive figure to an assertive leader is a significant aspect of the story. How do you illustrate this journey?

The Exchange Place podcast is envisioned as a three-year series. In this first season, we weave the story of several alumnae with the story of the founding of the school. As part of the school’s story we explore Alice’s decision to join a program that is a part of the Civil Rights Movement.

When she joins, it is a part-time position and she intends to go back to the public school system where she has security and a pension. In that part-time capacity she is mostly shielded from the politics and conflict that faces Father Tim Gibbons on a daily basis.

The last of episode of the first season is called, A Cowardly Lion. It’s about Alice’s decision to accept the full-time Director position and, as we say, become a full-fledged participant in the civil rights movement.

The school was shut down due to financial constraints, and there’s talk of a conspiracy reaching the highest levels of government. How deep do you dive into this controversy?

This story, the story of the school being shut down for a second time, will be covered in the second season of the podcast. It is informed by, amongst other sources, the Wall Street Journal reporter who investigated the school in 1967 and authored a front page article about the school.

The Journal decided not to go deeper into the political shenanigans that led to the school’s closing because ‘corruption in Louisiana politics wasn’t as big a story as Black women getting secretarial jobs.’

Alice’s life was intertwined with the civil rights movement, yet she never actively participated in it. How do you reconcile this dichotomy in telling her story?

The Adult Education Center was a pivotal program in the fight for equal job and adult educational opportunities. For many, equal job opportunities was the ultimate promise of the civil rights movement. So, Alice did become an active and well-known participant the civil rights movement and was recognized as such.

For instance, she was honored with the Martin Luther King, Jr. Torchbearer’s Award. In her succeeding job as the first director of Career Education in Louisiana, Alice continued this fight. And in all her succeeding jobs, too. Exchange Place tells the story of how she comes to be one of a handful of White women in New Orleans to take on this fight.

As a reflection of this, when dozens of New Orleans public school facilities named after slave owners and other anti-democratic figures were to be renamed, there was a nomination process for alternative names. Amongst the finalists, Alice was the only White woman to be nominated.

Ultimately, a building that would house the $32 million New Orleans Career Center located in the historic Tremé section of the city would be named in her honor.

Alice’s relationship with Father Timothy Gibbons seemed complex, even romantic. How do you represent this aspect in your series?

“Complex, even romantic” is a great way to describe their relationship. Tim was a young, charismatic man of the collar with a Master’s degree in psychology. We explore his relationship with Alice in the first season by describing the many reasons why Alice became so fond of him. When she was unsure of joining him, he challenged her, asking her bluntly, “What have you done to deserve your reputation?”

When she did join, as his secretary, Tim treated Alice as an equal and deferred to her experience as a business educator. This, at a time when many women were first entering the workforce, but mostly as subordinates. Tim showed Alice that he believed in her abilities by putting her in positions where she could put her talents to full use.

It was Tim who championed her as the Director when others thought someone with more experience and political savvy should get the job. Later in the series we explore how their relationship changed and finally came to an end when he left the priesthood and married a former nun.

Can you explain why Alice suddenly stopped working on her book about the school?

In “Why Now, Why Us,” the third episode of Exchange Place, I give a first-person account of the reasons we believe Alice stopped working on the book. I think the number one reason was that she was confounded by the persistence of what, in 1972, she called the Four Horseman of the Twentieth Century…Poverty, Pollution, Prejudice and Political Expediency.

In 2003, in the first decade of the Twenty First Century, those problems were still far from being expunged. In fact, the growing disparity between rich and poor and mass incarceration made it seem worse. On top of that, she knew full well from first-hand experience that inequality of all kinds were a fact of American life. She loved writing and she loved reconnecting with her former students to get an update on their lives.

The more she did so, the less she understood why the will to eliminate poverty and other problems had come to be seen as old fashioned and naive. Why were the poor, Black and White, being villainized, stereotyped and scapegoated. She could not reconcile her own experience with a supposed post-racial neo-liberal society. There was a time in her life when she was in a position to write history.

She no longer felt she could do so. She reached out to Tim Gibbons to collaborate with her. To help her come to terms with the philosophical and political implications of the school’s message. When he declined, she stopped writing.

How do you hope to bring to light the experience of Pamela Cole Wimbley and her sisters through your series?

Episodes 10 and 11 of the series are, respectively, The Cole Sisters, An American Family and Ms. Pamela Cole: A Working Life. The format for the two episodes is what I would describe as a Terri Gross style in-depth interview with Pamela Cole, the youngest of the four Cole sisters to attend the Adult Education Center.

In Pam’s own words, The Cole Sisters tells the story of her family, especially the idyllic and non-stereotypical relationship between her enigmatic conservative father and her hard-working mother; and Pam’s three sisters, all of whom attended the Adult Education Center.

By simply telling the story of her family, Pam relays what we mean when we say that the students of the school were nurtured and given their strong values by the African American communities where they grew up. These communities survived and thrived despite lacking resources, political power, equal access to services, educational opportunities and jobs.

The Cole’s story opposes the cliché depictions of people growing up in the projects and poor neighborhoods of New Orleans. If the Cole’s are disadvantaged, a technical term used to describe the Center’s student population by the federal government, it is not disadvantaged in terms of love, caring, ambition and the high value they placed on education and hard work.

In this and other stories, we assert that the Cole’s were not atypical of New Orleans Black family life, but emblematic of it and, equally, the American Dream of the 1950’s.

In Episode 11, Ms. Pamela Cole: A Working Life, Pam tells the story of her working life as she integrates one office after another, from New Orleans, to New Jersey, New York, Huston and Atlanta. In so many of these work environments, Pam is the only Black woman, or one of the few even by the late 1970’s. In one office, she is relegated to working in the equivalent of a storage room, out of view, because there is another Black woman. The bosses don’t want it to appear that there are more than one in the corporate office.

In other instances, Pam faces overt discrimination in terms of advancement and pay. Pam’s experience has a haunting parallel to the statistical analysis in the groundbreaking work by Donald Tomaskovic-Devey and Kevin Stainback, Documenting Desegregation: Racial and Gender Segregation in Private Sector Employment Since the Civil Rights Act. In that work, the authors use statistics gathered since the Civil Rights Acts of 1964 and 1965 to track desegregation.

What they find is that desegregation in the workplace flattens out starting in 1980 especially for Black women. While companies are technically desegregated, Black women in particular are relegated to lesser positions with fewer opportunties to climb the corporate ladder. The companies are segregated within. Meanwhile the private financial sector that grew so steadily after 1980 to this day is highly segregated.

Time after time, Pam transcends discrimination to fulfill her own ambitions and destiny. This episode is an intersectional story, a story about being a working woman and a working Black woman in the United States over the past six decades. At the time the podcast was recorded, at the age of seventy-five, Ms. Cole was still working full time.

The school emphasized strengthening self-image along with imparting critical technical skills. How will you convey this balance in your portrayal?

Exchange Place has five episodes that are first-person accounts as told by the alumnae themselves. All of those interviews are structured in four parts. The first part is “Early Life”; the second is “Adult Education”; the third, “Working Life”; and the last is “Now and the Future.”

In Adult Education the alumnae discuss details about the curriculum. As such they talk about everything from the intense classes on hard skills such as typing, shorthand and speech to the soft skills they learned in what they called “charm class,” but the school called Personal Dynamics.

Then, in the subsequent parts we see how these skills were used in interviews, on-the-job and even today. Without exception, each alumnae’s favorite class was Personal Dynamics, where the women explored everything from personal hygiene and hairstyles to their feelings about the pill.

In this class, feelings about self-image are intertwined with hard skills to bolster self-image such as learning how to accessorize a single dress into multiple outfits for a five day a week job.

The unique challenges that Black women must deal with in terms of hairstyles and makeup were explored in depth, thus giving the students a sounding board to address their curiosities and insecurities.

In a world where a Black woman arriving at an office wearing an Afro was seen as a provocation, the Center was a place to explore how to overcome such a panic and not lose site of one’s own identity. As Pam Cole said when she went out for a job at Shell, “my hair is not going to do the work.”

Alice had a series of “miniographies” about the success of her students. Will these anecdotes play a role in your project, and if so, how?

Alice’s miniographies play out in the first-person accounts of the alumnae. Each alumnae tells anecdotal stories how a good paying job with benefits changed their lives and self-esteem, from being able to buy a house, a car, paying for college education for their children or being able to enjoy travel.

The theme that runs through all the stories is that there is a correlation between a good job and a feeling of self-worth. For those students who were previously on welfare, this feeling is especially dramatic.

What impact do you believe Alice’s work at the Adult Education Center had on her subsequent work in career education?

As with her involvement in the Civil Rights movement, Alice was ahead of her time when it came to her hopes for the future of education. She believed in the concept of a confluent education.

She was in favor of an educational system where career and vocational education coexisted with higher education in terms of status and priorities. She believed that students should explore careers via on-the-job training at an early age, in professional and vocational jobs, and throughout their high school careers.

She believed that the path to a high quality of life should not be determined by the decision to go to college at an early age versus going into a vocational career. She was concerned about the rising prices of both vocational and higher education and the impact that substantial loans could have on the quality of life of the student and the shape of society.

Therefore, she believed it was important to put even college students in the position to earn a good living while they went to school by teaching them valuable skills in high school.

Likewise, she believed in the necessity of lifelong learning. She could see how the world was evolving in such a way that a few years of education early in life would not be adequate for a society undergoing exponential change and where specialization was increasingly the norm.

In other words, the student that chooses a vocational path at an early age should have the opportunity to pursue higher education later. Likewise, that graduates of higher education should be entitled to explore other skills, including communication and interpersonal skills, even if they are settled into one specialty or another. She believed in a holistic form of education, in both career and higher education.

That is, the importance of focusing on the well-being of the student and the teacher in the process of education. This approach to education became manifest in her role in funding and supporting a series of career educational programs across the state of Louisiana, one of which became the prestigious New Orleans Center for the Creative Arts (NOCCA).

How do you intend to honor the legacy of Alice Geoffray and the 431 Exchange through your upcoming book and television series?

In honoring the alumnae of the Adult Education Center we honor the legacy of Alice Geoffray and our non-profit fund. In amplifying their voices, their names, their courageous stories to a wider public, we bring something of value to our audience.

The alumnae inspired my mother to be her best self; they are our moral compass today. We know their stories will inspire others who seek to transform their lives through education, as well as show how teachers and their supporters play a crucial role in the lives of students forever.

The story of the Adult Education Center is one of triumph against societal norms and systemic racism. What message do you hope viewers will take away from this story?

In the preface to Malcolm Gladwell’s book, Outliers, he says that his book is the story of the forest, not the trees. He tries to explain the complex relationship between individual opportunity and the society that makes such an opportunity possible. Exchange Place is also a story about the forest.

It is the story of the resilient African American community that raised the beautiful women who are the subject of the podcast; the new laws that, at least on paper, removed technical barriers that prevented these women from obtaining jobs that matched their ambition and ability.

The visionary teachers, administrators, clergy, government bureaucrats and businessmen who leveraged small changes in laws and society to help the Center’s students manifest their dreams; and, finally, it’s about the graduates themselves, who seized opportunity once it was within their grasp.

In summary, we hope our audience will take away this message from our podcast:

Building a just society with equal educational and career opportunities for all its members is not inevitable – to reach this goal every institution must be aligned in favor of it, each individual must play a part in making it happen.

Lastly, if Alice Geoffray were here today, what would you like to ask her or tell her about this project you’re undertaking?

I would ask her about some of your questions! For instance, how did her work at the Adult Education Center inform her later work.

How did her views on education change over time, especially in the process of getting her Master’s degree and Doctorate? Last, does she think our approach to telling the story of the Adult Education Center through the biographies and autobiographies of the people involved honor her legacy and the truth.