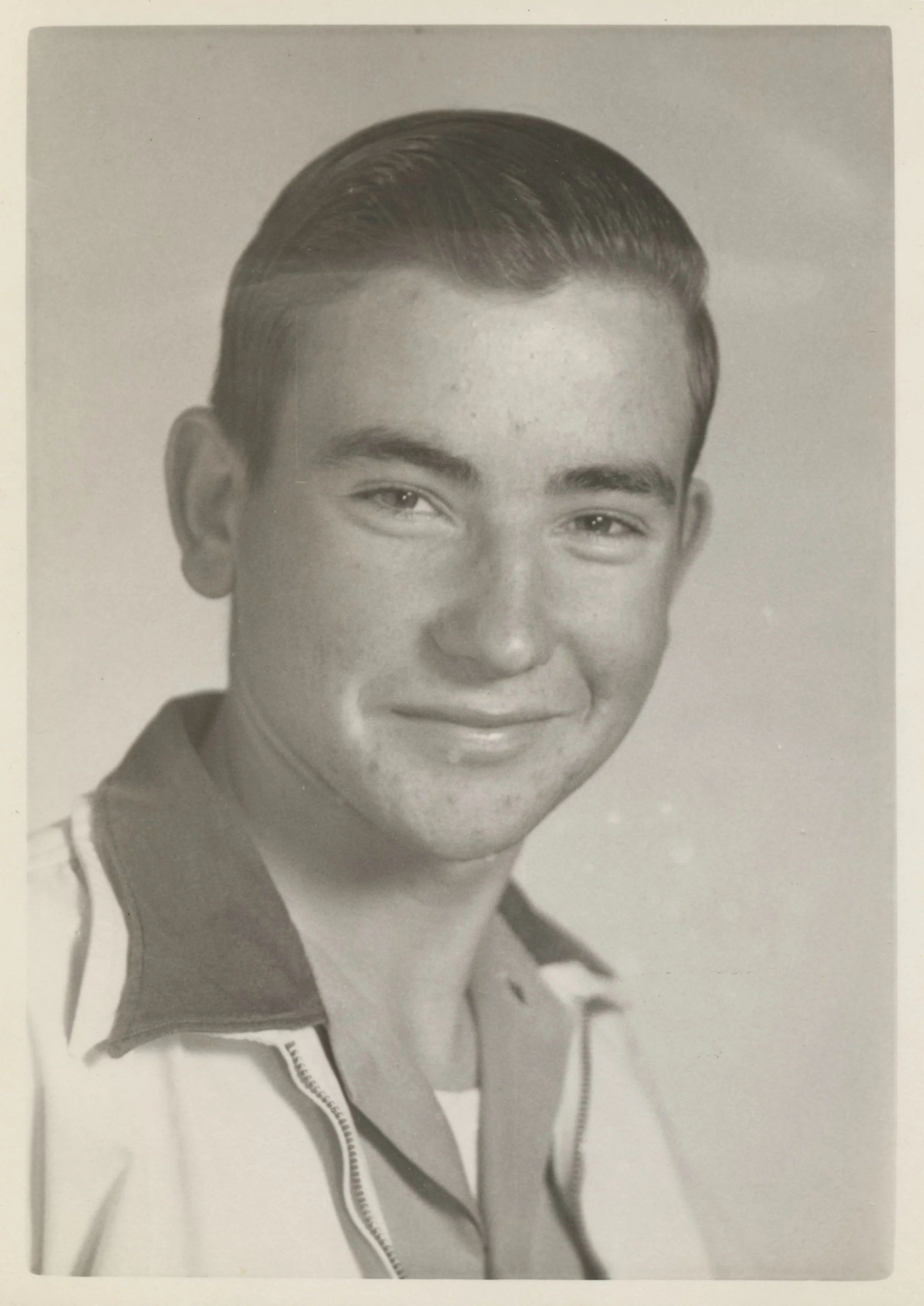

Floyd McLamb at 90 – A Life in Full Color

From the fields of North Carolina to the heart of the French Quarter, former Adult Education Center teacher, Floyd McLamb’s life is a testament to quiet rebellion, creative fire, and radical empathy.

Click on any image to view it larger.

Introduction

“The best gifts are the ones no one sees.”

At 90 years old, Floyd McLamb isn’t just a survivor—he’s a storyteller, a giver, a Southern original. Born into poverty during the Great Depression, Floyd forged a path that defied expectation: a gay man from rural North Carolina who became an entrepreneur in New Orleans, a beloved teacher in a landmark civil rights school, and an award-nominated writer whose fiction is as raw and wise as the man himself. As he celebrates his 90th birthday, we look back on a life of grit, humor, and grace—and forward to a legacy that continues to inspire across generations.

Profile of Floyd McLamb; entrepreneur, teacher, world traveler and author. Floyd's lifelong track record of generosity is an example for those who would search for peace in their own lives by giving to others. Floyd was an English teacher at the Adult Education Center in and around 1968.

Early Life: “A Stranger to Himself”

“The holy trinity in our household was hunting, cockfighting, and drinking.”

Floyd McLamb was born in 1935 in the cotton mill town of Erwin, North Carolina—into a world of hard work, harder men, and religious certainty. “My family wasn’t affected by the Great Depression,” he later joked. “We were already living it.”

The youngest of six, Floyd grew up on a 17-acre farm his father purchased to escape the mill and raise crops. Instead of open fields and promise, Floyd found himself trapped in a world that seemed both physically and emotionally punishing. His mother was devout, self-sacrificing, and often joyless. His father was volatile and cruel. “The holy trinity in our household was hunting, cockfighting, and drinking,” Floyd wrote. And he was expected to follow suit.

Click on any image to view it larger.

But Floyd was different. He failed the “supreme test of manhood” when he recoiled at killing a hog, splattered in blood and fear. “Maybe I was already a sissy and didn’t know it,” he quipped. His sisters teased him for being too sensitive. His father would later raise a rifle at him during a violent argument. And still, Floyd persisted—drawn to literature, library books, stamp collecting, and typing.

Even as he endured childhood abuse at the hands of an older cousin—abuse he only years later had the language to name—Floyd quietly began assembling the building blocks of selfhood. He found beauty in small places: trimming calluses from the feet of a disabled relative, memorizing the cadence of “In Flanders Fields,” or savoring his first view of a TV set on a neighbor’s farm.

At 17, he volunteered for the Army during the Korean War, trading rural isolation for boot camp, Panama, and the bittersweet clarity of first sexual encounters—none of which he could name aloud. “In the Army,” he wrote, “you could be anyone…as long as you didn’t ask why.”

From there, Chapel Hill opened up a different world: poetry readings, avant-garde theater, secret bathroom encounters, and finally, a tentative community of young gay men navigating the South’s treacherous geography of repression. Floyd typed 90 words a minute, read Sartre and Gertrude Stein, and dreamed of love.

But even amid sexual awakening, the “lonely road” endured. Floyd described himself not as unloved, but “as a stranger to myself.” He would later find success as a teacher, writer, and entrepreneur—but the seeds of his generosity and grit were sown in red clay and silence, long before New Orleans ever heard his name.

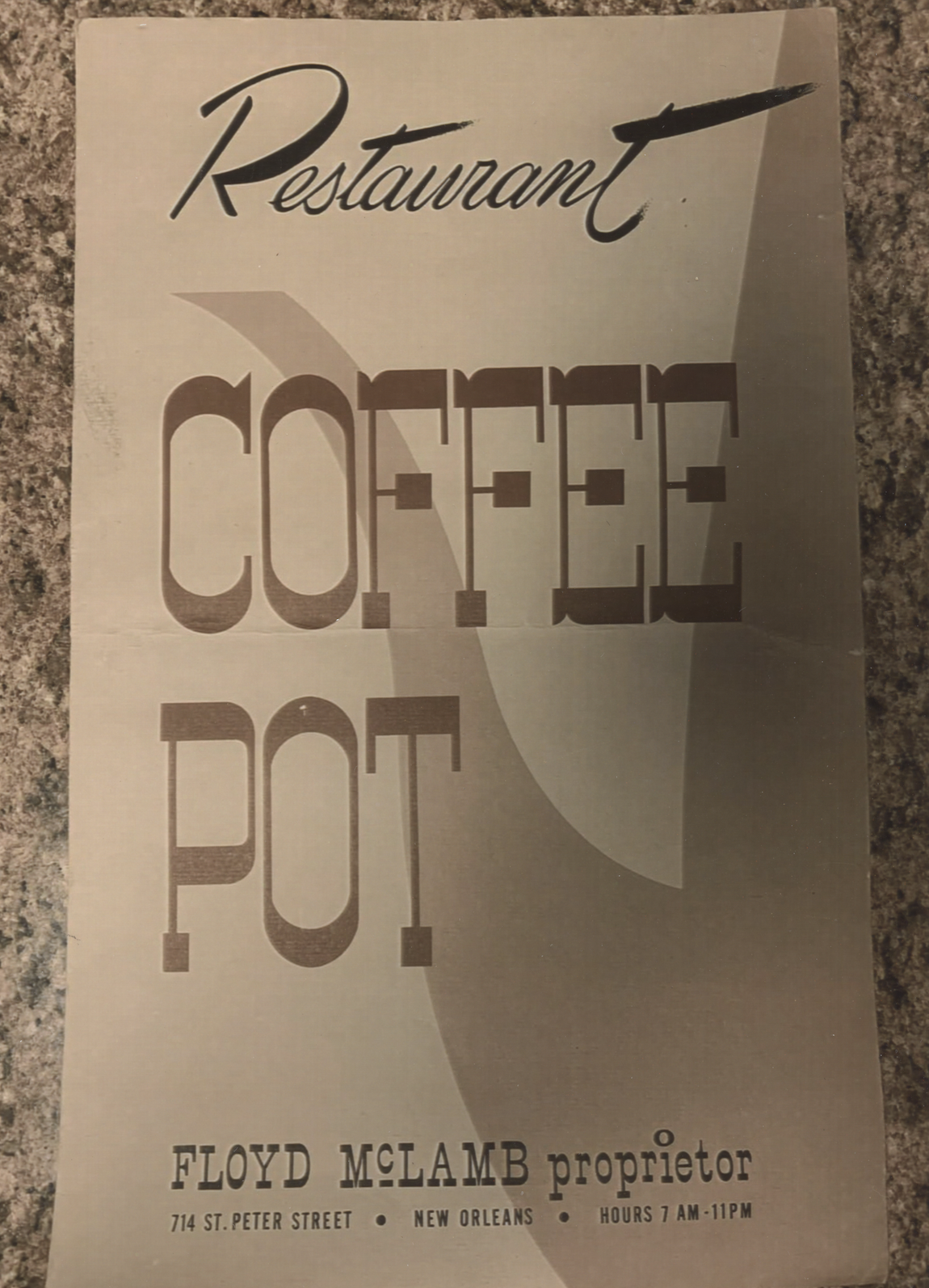

The Quarter Was My Canvas

“What does a small business have but its personality?”

When Floyd McLamb bought The Old Coffee Pot café in the French Quarter, he wasn’t looking to start a business—he was trying to rescue one. He had already been a teacher, a typesetter, a wanderer. But the Quarter drew something different out of him. Something permanent. Something bold.

The Coffee Pot was floundering when Miss April handed Floyd the keys for the summer. He stabilized it with what he knew best: relentless labor and Southern charm. “What does a small business have but its personality?” he liked to say. Floyd repainted the café himself, slept between shifts on tablecloths, and ran the joint from 6:30 a.m. to 11 p.m. daily. When a waitress complained about impatient tourists, Floyd snapped, “I’m getting damned tired of this.” The waitress relayed his words verbatim. It worked. The tourists stayed, and more came, along with many locals who soon became regulars.

That was Floyd’s magic. Honesty, humor, and hard work, poured into one cup of coffee at a time.

Click on any image to view it larger.

He didn’t stop there. The café’s alleyway soon became a showcase for young artists, then across the street, The Paint Pot, an art gallery showcasing local painters like Noel Rockmore. Around the corner came The Glue Pot, a framing business. Then a bar. Then a restaurant. Then another gallery. “My career,” he said later, “was just one good idea bumping into another.”

The French Quarter became his ecosystem—and he became one of its mythic figures. He created space for eccentricity and community. Artists gathered at “The Family Table.” Hippies drifted in for free water and conversation. Tourists left with art they hadn’t meant to buy. And Floyd, ever the provocateur, became a brand of his own: quick-witted, unfiltered, and unapologetically himself.

Today, Floyd’s early business ventures live on as cultural landmarks—if not in deed, then in memory. As French Quarter Journal writer Andrew Cominelli put it: “Floyd is the only person I’ve ever met with a bona fide Horatio Alger story.”

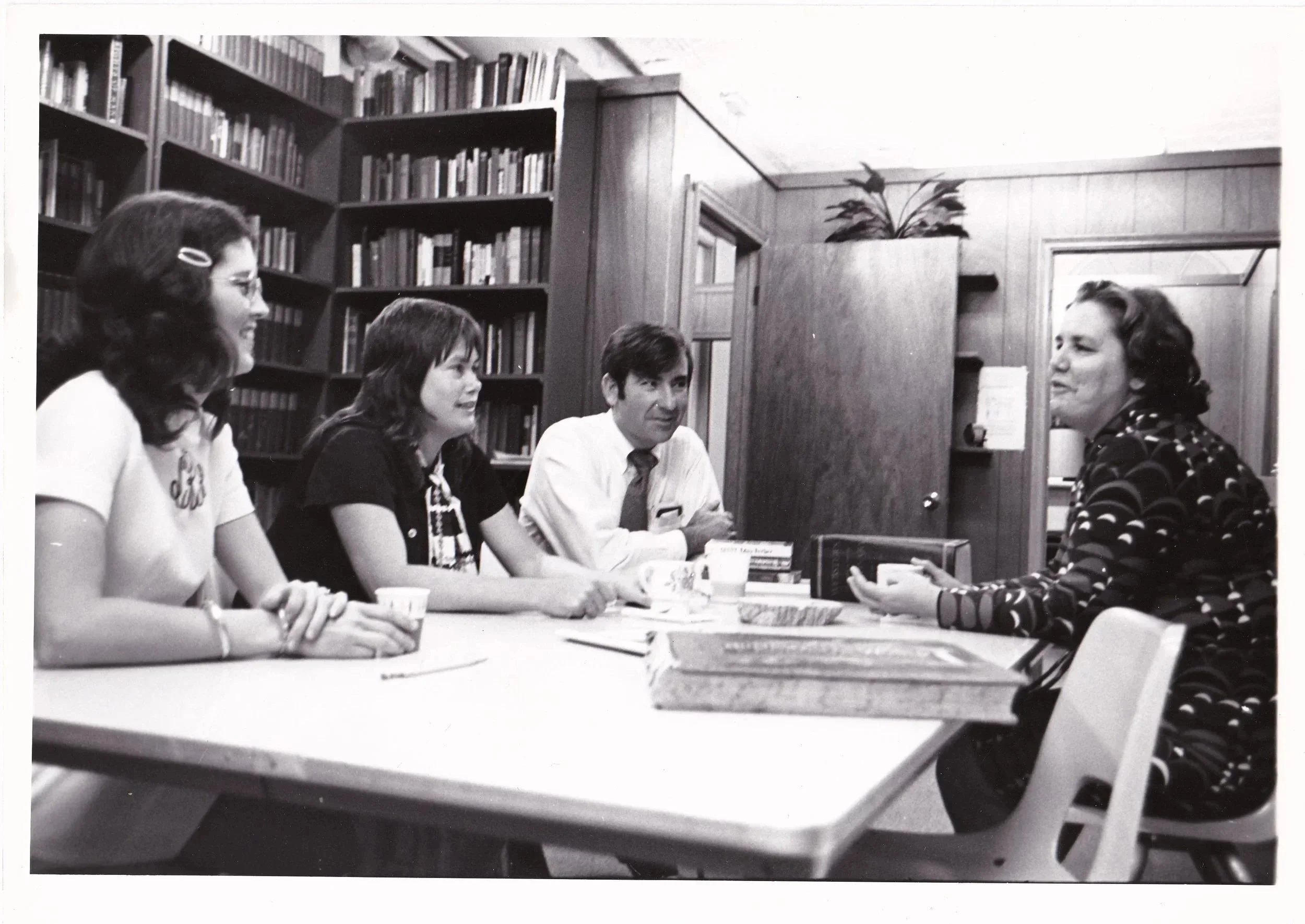

The Teacher

“I think the students knew that I cared—and I think that’s more important than anything else.”

Before Floyd McLamb was a celebrated entrepreneur or memoirist, he was a teacher—and not the kind you forget.

In 1968, just as the Civil Rights Act was reshaping the South on paper, Floyd was helping to reshape it in practice. As a part-time English teacher at the Adult Education Center in New Orleans, he stood at the front of a classroom filled almost entirely with Black women—most of whom had never had a white teacher. He wasn’t trained for the job. He hadn’t set out to be an educator. But when Alice Geoffray asked him to join the Center, Floyd said yes.

Click on any image to view it larger.

“I didn’t think I was qualified,” he later said, “but the students knew I cared.”

And they did. That care wasn’t loud or performative. It came through in small, unforgettable acts. He once sold a painting and used the profits to secretly give each student ten dollars for Christmas. When he learned that one of his best students, Hilda Jean Smith—a 24-year-old raising 15 children—was struggling to stay afloat, he anonymously gifted her $300, asking only that she spend it on herself. She wouldn’t find out for decades that it was Floyd.

On the surface, they couldn’t have been more different. He was a single white man, a gay entrepreneur juggling antiques and art galleries. She was a Black woman from New Orleans who had stepped into the role of matriarch after her mother died when she was 16. And yet, they understood each other.

“We both came from hardship,” Floyd said. “We both wanted something better—not just for ourselves, but for everyone around us.”

The bond between Floyd and Hilda would last a lifetime. Their friendship, featured in the short film, Acceptance, is a rare portrait of what happens when empathy transcends difference. They laugh together, reminisce, and remind us what solidarity can look like when it’s grounded in humility, not ego.

Floyd’s classroom style was unconventional. He didn’t hide his nerves or pretend to be an expert. “The first day I talked about subjects and verbs,” he said, “and I saw their faces and thought, ‘Oh hell, you’re in deep trouble.’” But what he knew what his students lacked in grammar they made up for in desire and tenacity.

He edited the school paper. He encouraged students to write poetry. He remembered each one. And even after he left teaching to run the Coffee Pot full-time, Floyd kept coming back—to listen, to support, to keep the door open.

He would later say that teaching at the Adult Education Center tapped into his deepest values: helping people, judging them by who they are—not what they’ve been told they’re worth. “I still try to judge the person,” he said. “Not the master’s degree. Not the color.”

In a world where many talk of equality but few risk discomfort for it, Floyd McLamb showed up, paid attention, and gave quietly. And that, as any teacher will tell you, is the real lesson.

The Writer

“Some folks get religion. I got the need to tell stories—and the good sense to make ’em short.”

Floyd McLamb’s writing doesn’t whisper. It doesn’t posture. It speaks, sings, shouts—and always from a place of hard-won clarity.

In his memoir The Lonely Road, Floyd traces his own journey from the cotton fields of Depression-era North Carolina to the gay bars of New Orleans and beyond. It’s a sexually frank, emotionally honest portrait of a man who refused to be anyone other than himself—even when he didn’t yet know who that was. His voice is droll, poetic, unflinching—and as one reviewer put it, “brilliantly universal.”

That same voice permeates his fiction. In Aunt Loretta Is Dead, Floyd offers an elegy wrapped in a child’s awakening. Uncle John’s ritual care of his deceased wife—whom he still sees as the radiant girl he fell in love with—exposes the cruelty of religious shame and the persistence of love. The story lingers long after its final line, reminding us that devotion can outlive even bitterness.

In Band of Gold, he paints a portrait of a woman who uses the system—quietly, cleverly—to escape the same kind of prison Floyd knew as a child: a home filled with rage and resignation. Her smile at the end, twisting a ring that finally means something, is a signature Floyd moment—resigned, knowing, victorious.

And then there’s A Fistful of Freedom, where Merle, a mother and wife bound by expectations, finds her voice in the French Quarter. Inspired by the sales pitch of a carnival artist, she transforms from invisible homemaker to street painter with a point of view. Like Floyd, she knows the world won’t give her a seat at the table—so she makes her own.

These aren’t just stories. They are resurrections. Floyd writes working-class women with such tenderness and grit you’d think he’d lived beside them—and he did. His prose honors what society overlooks: women without money or degrees, men with broken pasts, people made wise by trauma. Through them, he lays bare the values that define his life: kindness, integrity, self-reliance, and a quiet insistence on joy.

It’s no surprise that one of these stories—Aunt Loretta Is Dead—was a finalist for the William Faulkner – William Wisdom Creative Writing Competition.

McLamb’s characters may live in ramshackle cabins, shotgun houses, and artist stalls—but they speak with the authority of prophets. They know what it costs to tell the truth. And they tell it anyway.

Later Life: High Cotton, Clear Eyes

“I have worked hard, but I am enjoying my old age... I am alone a lot but I’m very happy.”

For many years, Floyd McLamb made his home on a quiet stretch of land in Poplarville, Mississippi, which he proudly named High Cotton. It’s an old Southern phrase meaning “doing well for oneself,” but in Floyd’s case, it has always meant more than comfort—it meant living with purpose, creativity, and a spirit of giving.

Well into his 80s, Floyd was clearing land, planning gardens, hosting writers’ gatherings, and nurturing friendships that stretched across generations. While his health has recently required a slower pace, the essence of Floyd—the storyteller, the giver, the keen observer of life—remains fully intact.

Surrounded by friends in Mississippi, Louisiana, and around the world, Floyd continues to inspire those who know him best. His days may be quieter now, but his presence remains a powerful force.

Legacy & Love: The Quiet Architect

“She was not the only girl looking at his slicked-back hair, his big broad smiling face, and his too-tight pants.”

Floyd McLamb has shaped more lives than most of us will ever know.

From his early days as a teacher at the Adult Education Center to his ongoing support of the 431 Exchange, Floyd has made generosity his life’s quiet signature. He is a major donor to the scholarship fund, a mentor to many, and a steadfast supporter of the students who remind him of those he once taught—and of the young man he once was.

But his greatest legacy may be the web of relationships he has woven over the decades. Former students, fellow artists, business partners, and dear friends across states and continents speak of Floyd with reverence and affection. Whether through a story, a quiet act of kindness, or a well-timed joke, he has left his mark not just on a school, but on a world of people.

Floyd once wrote that the best gifts are the ones no one sees. At 90, he is still giving them.

Floyd McLamb

“She twisted the band of gold on her finger and smiled.”