Every Woman from A to Z

By Evelyn C. White

The secretarial profession can be traced back to the Roman Empire when men who then prevailed in the position were extolled as trusted scribes and confidants to other powerful men such as magistrates and priests. The scribae “gained [clout] which they not infrequently abused,” notes the Oxford Classical Dictionary.

In North America, women began to secure work as secretaries in the late 1800s. The gender shift was fuelled by the invention, in 1868, of the first commercially successful typewriter, an industrial breakthrough that prompted many women to pursue clerical jobs.

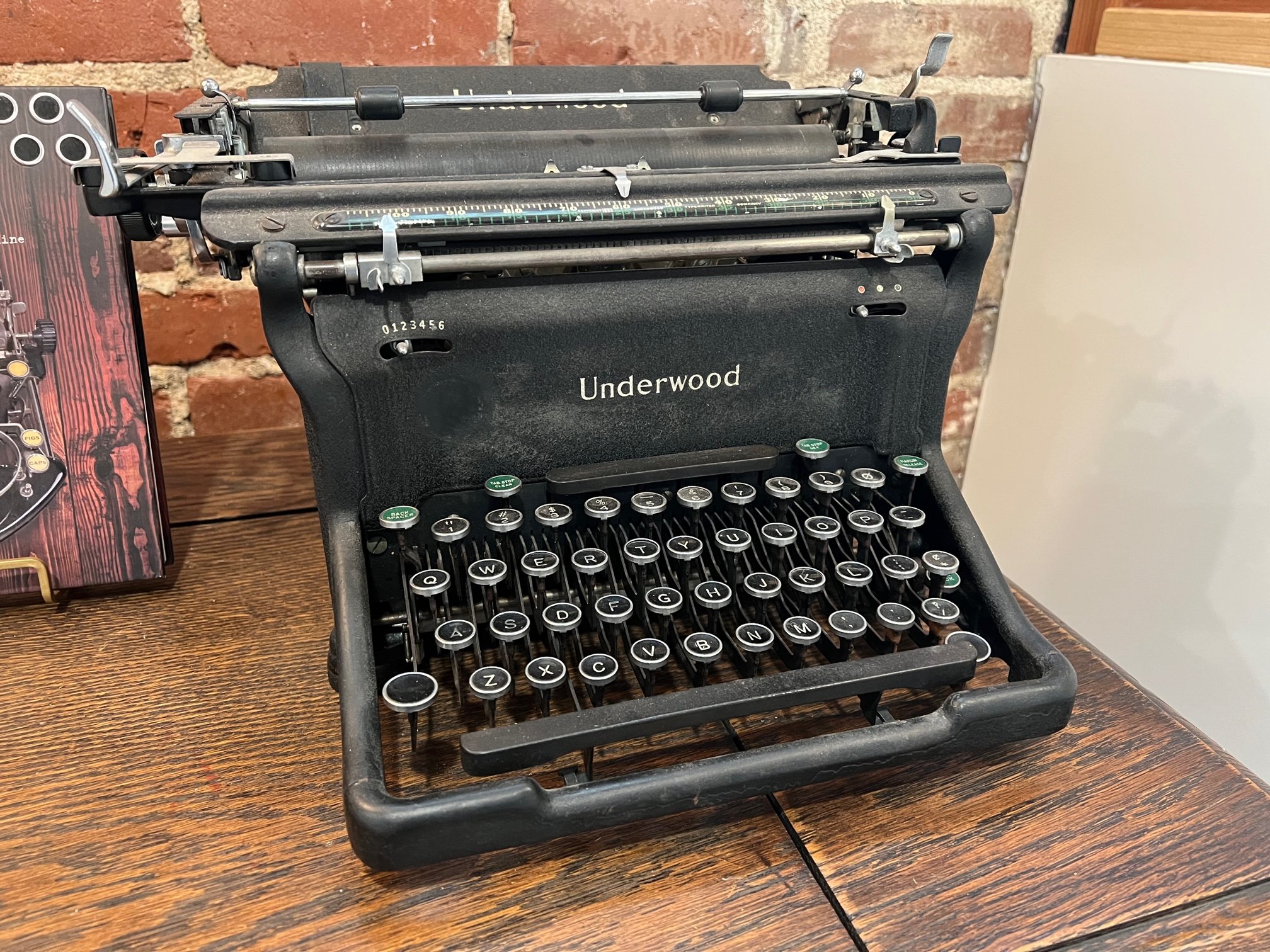

A version of the Underwood 2 of 1897.

In his book Typewriters: Iconic Machines From the Golden Age of Mechanical Writing, Anthony Casillo delivers an absorbing history of the device. The volume also includes a foreword by actor Tom Hanks, an avid typewriter collector.

By the 1930s, women held the majority of secretarial positions in office settings, both large and small. The National Secretaries Association (now the International Association of Administrative Professionals) was founded in 1942 to promote continued education for clerical workers and to increase career opportunities in the field. A decade later, the group initiated Secretary’s Day (since renamed “Administrative Professionals Week”) which is now annually observed, in April, in offices from Minnesota to Malaysia.

The Bureau of Labor statistics estimates that nearly 4 million people hold secretarial jobs in the US and earn a median yearly salary of about $41,000.

Along with the typewriter, tools of the trade for clerical workers (before computers) included stenographer pads, in which secretaries took dictation from their bosses, in shorthand. Then there was the ballpoint pen, a writing instrument infinitely more reliable (and less messy) than a fountain pen.

“The Bureau of Labor statistics estimates that nearly 4 million people hold secretarial jobs in the US and earn a median yearly salary of about $41,000.”

As for fountain pens, those who watched last week's State of the Union address by President Joe Biden, might have noted the silver inkstand that sat in front of House Speaker Nancy Pelosi. The stand reportedly dates back to 1810-1820 and would have been used to hold ink, writing instruments such as quill pens, and a pen wiper. John Hancock reportedly used an inkstand to affix his distinctive signature to the Declaration of Independence.

Improving on the ballpoint pen mechanism first patented by Lásló Biró in the late 1930s, French entrepreneur Marcel Bich created the hexagonal BIC Cristal pen, in 1950. Priced at 29 cents, BIC pens entered the American market in 1959, with the slogan “writes first time, every time.”

In September 2006, BIC recorded its 100 billionth sale, making it the best-selling ballpoint pen in the world. Like the Slinky, the BIC Cristal is in the permanent collection at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.

The aspiring secretaries who studied, from 1965 to 1972, with Alice Geoffray and her staff at the Adult Education Center were sure to have found an office supply closet chockablock with BIC pens. Indeed, I recently noted that a ten-pack (seven blue, two black, one red) retails for $1.99 or 19 cents each. Less than the original price!

As we mark International Women’s Day, I find myself reflecting on a pre-Covid visit I enjoyed with one of the few female executives in the world of ballpoint pens. Namely, Susanne Christensen, sales manager and co-owner of the Eskesen company in Store Merløse, Denmark (about an hour outside of Copenhagen).

“Like the Slinky, the BIC Cristal is in the permanent collection at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.”

Founded in 1946, Eskesen thrives on a floating action pen or “floaty” that bears the stamp: Made in Denmark. However, the insignia often goes unnoticed by those who’ve purchased the item at gift shops or who’ve found it among the promotional swag at international trade shows.

A paragon of Danish functionality and innovative design, the ballpoint pen features a small image of, say, the Pike Place Market (Seattle), a Dixieland band (New Orleans), or a lime-filled glass (One With Life Organic Tequila). Tilt the pen and the picture glides through a window on the pen cartridge. Reverse tilt and the image floats the other way.

“This is where it all happens,” Christensen said, as she led me through a sunlit room in the compound where her predominantly female staff produces nearly 2,000 float pens an hour. “There are Eskesen collectors all over the world and every pen has been designed, assembled, and shipped from this facility.”

Then Christensen escorted me into another room that was stacked high with metal barrels. There, she cautioned me to watch my step. “The floor is very slippery,” she noted, with a wink.

Later, over a traditional Danish lunch of smørrebrød (elaborate open-face sandwiches), Christensen recounted the history of the company that was launched by Peder Eskesen, an unassuming manufacturer who saw promise (and prosperity) in a material both lightweight and strong — acrylic plastic.

In the early 1950s, Eskesen secured a contract from Esso (Standard Oil) to develop a marketing tool for the company’s mainstay product — motor oil. Inspired, Eskesen hand-crafted a miniature oil drum that he placed inside a “see through” acrylic tube filled with mineral oil. He then fitted the device with the mechanism for a ballpoint pen.

With the flip of a wrist, the tiny oil drum “drifted” back and forth through the pen which Eskesen affixed with a foolproof (think Fort Knox) seal. “The pen didn’t leak, break, or scratch,” Christensen proudly declared. “Other people saw the Esso float pen and orders started flooding in from all over the world.”

Fluent in French, German, and English (along with her native Danish), Christensen joined Eskesen in 2005 after an executive career with an international paper products firm. Mindful of her ascent in the male-dominated world of manufacturing, she noted (with rightful indignation), competitors who’ve attempted to muscle in on Eskesen’s float pen magic.

“I’ve gotten angry complaints from people whose shipment of pens arrived broken or frozen,” Christensen told me. “I’ll gently remind them that the pens are not from my company.”

“Eskesen pens are the only ones made with mineral oil, which does not freeze,” she continued. “We store it on site, in the room with all the barrels. So, I tell the upset people that if they’d bought authentic float pens instead of cheap ones filled with water, there wouldn’t have been a problem. All of the companies selling fake pens eventually fail.”

At a time when completing homework assignments or writing love letters by hand has become passé, pens stamped Made in Denmark have achieved a remarkable cachet. “A pen might seem outdated when you can connect electronically on a computer or a cellphone,” Christensen said, at the end of our delightful visit. “But there are fans and collectors who are wild about Eskesen pens.”

Indeed, an Eskesen float pen makes a cameo appearance in the most recent James Bond 007 film, No Time to Die. “In the beginning of the movie, they are in a hotel and the woman sits down to write a note,” Christensen explained, in an email. “It is only shown for a few seconds. But this is our pen and we are beyond proud.”

A former reporter for The San Francisco Chronicle, Evelyn C. White is the author of Alice Walker: A Life (WW Norton, 2004).